Article about the exhibition of Ana Sluga: Spatial Dissonance (Choice) that took place at Galerija Kresija, Ljubljana (19 January – 23 February 2021)

A silhouette of a military aircraft dropping bombs into free fall can be seen as an unambiguous synonym for total war, warfare that will use any means to achieve its ends. The image works as an anti-war poster employing clear and straightforward messages in an attempt to arouse compassion. It also alludes to the responsibility of whoever pulled open the bomb bay door and let the bombs pour out of the belly of the aircraft, even if merely following orders rather than acting of their own accord.

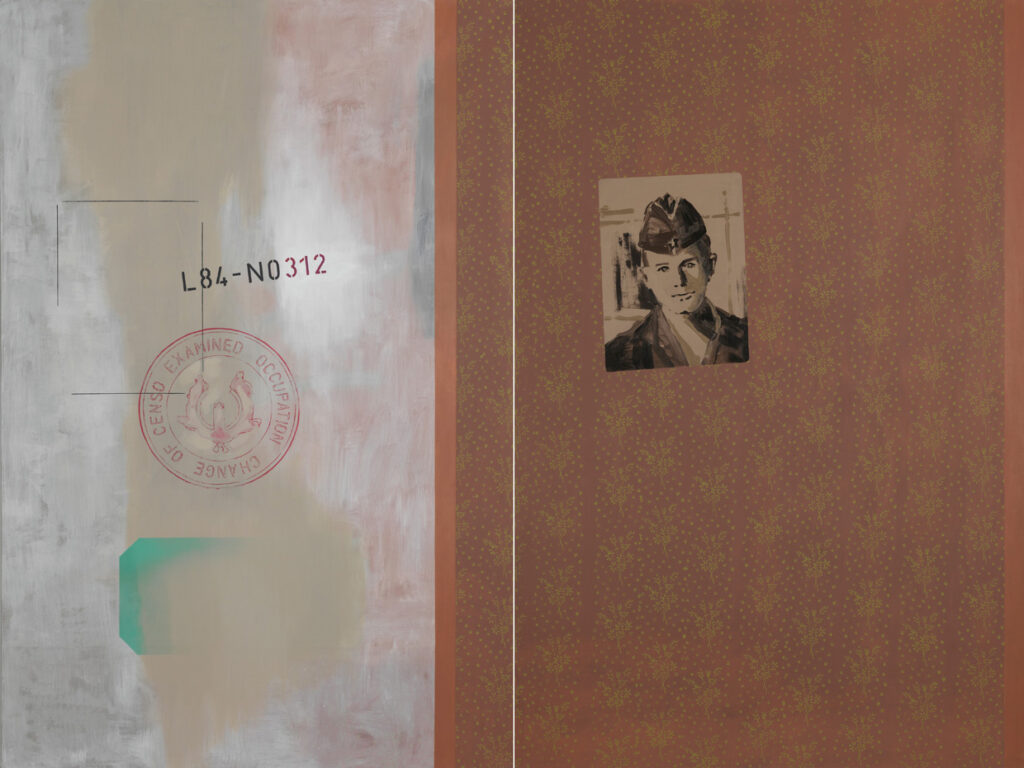

This is a motif used by Ana Sluga in one of the six paintings making up the polyptych entitled Spatial Dissonance (Choice) to suggest the direction and tone of her current art making. Hers is not an easy task, albeit dealing with conspicuous, omnipresent sociopolitical issues. How does one translate reflections on collective societal violence into effective visual communication? How does one tackle this age-old aspect of “human nature”, which invariably exposes humans at their worst? Although or precisely because today’s popular culture is saturated with images of violence, the individual has become increasingly insensitive to the traumas and adversity experienced by the Other, even if he or she might be (partly) responsible for them. In this cacophonous world where one is constantly bombarded with visual and verbal messages, it is difficult to elicit an emotional response and make fellow humans give their individual and collective responsibility for the ubiquitous violence a more serious thought. Sluga aims to do so by accentuating stylised images placed carefully onto monochrome or decoratively painted colour backgrounds. Advertisements are often structured in a similar fashion, by means of visual consonance, delivering ideas about the products they promote through highlighted images and messages. Yet what the artist attempts here is visual dissonance, aiming to spotlight some seeming modern-day givens. Her paintings, as familiar as they may appear at first sight, come with undertones that mostly arouse uneasiness.

By way of an artistic allegory, the painter explores the callous political decisions that drive societies into states of conflict. The dull, metallic colours dominating the paintings create an ambivalent, almost sinister atmosphere, only to be complemented by a collage of visual elements whose select fragments testify to systemic violence. The image of an official seal in one of the paintings implies the bureaucratic apparatus as the underlying principle of most of modern conflicts, as well as the role of the individual in the system; it hints at the relationship between decision-makers and implementers, and at the widening gap between the two roles. What you don’t feel, doesn’t hurt!

Modern-day conflicts are often based precisely on decision-makers being removed from the consequences of their decisions, and on policies with a top-down hierarchy. The head of a state that starts a war against another country and its people does not necessarily have to face the destruction and suffering caused by this war; the pilot who pulls open the bomb bay door might not personally feel the consequences of his or her actions. In recent years, an even more radical type of warfare emerged in the form of remotely controlled unmanned aerial vehicles, their operators sowing death and destruction from the safety of their control centres thousands of miles from the scenes of action, as if in a computer game.

Life or death decisions are much more comfortable to make indirectly than at first hand. When the Third Reich was implementing its genocidal policy of occupying territories in the east of Europe, the state apparatus trained special forces to be able to effectively eliminate hundreds of thousands of people on their mass murder sprees. After even the soldiers in industrial annihilation units experienced ethical doubts and psychological traumas, the authorities had to change their tactic and bring in quisling units to do the job, with the Third Reich soldiers merely guarding the massacre areas. In their own eyes, at least, this alleviated their responsibility.

War, however, is not necessarily an armed conflict. Class and ideological conflicts are continually underway in the so-called First World; particularly, in the last few decades, the struggle for complete subjugation of the masses. In such a war, violence is usually manifested as economic pressure on the working population grippled by the fear of losing access to the increasingly unaffordable basic necessities amid growing social pressure and expectations. Most citizens in neoliberal societies of today are under constant threat of experiencing financial hardship if they lose the possibility of having a meaningful and successful professional life.

With their metaphorical meanings, Sluga’s paintings allude to some of the most fundamental existential questions about violence and the role of the individual in society. This way, they spark debate on whether human nature is truly so vicious, heartless, and selfish that it is always the most immediate, short-term interests that ultimately prevail; and on whether it is truly that much easier to follow orders than to think for oneself.

© Miha Colner, January 2021